Dr. Ann McKee, a neuropathologist, has examined the brains of 202 deceased football players. A broad survey of her findings was published on Tuesday in The Journal of the American Medical Association. Of the 202 players, 111 of them played in the N.F.L. — and 110 of those were found to have chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or C.T.E., the degenerative disease believed to be caused by repeated blows to the head.

What is C.T.E.?

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE)is a brain condition associated with repeated blows to the head. It is also associated with the development of dementia. Potential signs of CTE are problems with thinking and memory, personality changes, and behavioral changes including aggression and depression. People may not experience potential signs of CTE until years or decades after brain injuries occur. A definitive diagnosis of CTE can only be made after death, when an autopsy can reveal whether the known brain changes of CTE are present. The problems can arise years after the blows to the head have stopped.

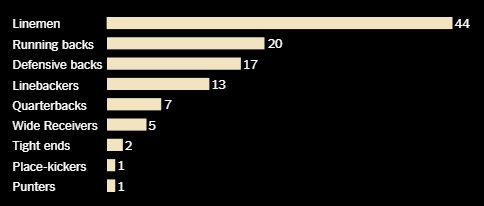

Positions with CTE

The brains here are from players who died as young as 23 and as old as 89. And they are from every position on the field — quarterbacks, running backs and linebackers, and even a place-kicker and a punter.

They are from players you have never heard of and players, like Ken Stabler, who are enshrined in the Hall of Fame. Some of the brains cannot be publicly identified, per the families’ wishes.

The image above is from the brain of Ronnie Caveness, a linebacker for the Houston Oilers and Kansas City Chiefs. In college, he helped the Arkansas Razorbacks go undefeated in 1964. One of his teammates was Jerry Jones, now the owner of the Dallas Cowboys. Jones has rejected the belief that there is a link between football and C.T.E.

The image above is from the brain of Ollie Matson, who played 14 seasons in the N.F.L. — after winning two medals on the track at the 1952 Helsinki Games. He died in 2011 at age 80 after being mostly bedridden with dementia, his nephew told The Associated Press, adding that Matson hadn’t spoken in four years.

Dr. McKee, chief of neuropathology at the VA Boston Healthcare System and director of the CTE Center at Boston University, has amassed the largest C.T.E. brain bank in the world. But the brains of some other players found to have the disease — like Junior Seau, Mike Webster and Andre Waters — were examined elsewhere.

The set of players posthumously tested by Dr. McKee is far from a random sample of N.F.L. retirees. “There’s a tremendous selection bias,” she has cautioned, noting that many families have donated brains specifically because the former player showed symptoms of C.T.E.

But 110 positives remain significant scientific evidence of an N.F.L. player’s risk of developing C.T.E., which can be diagnosed only after death. About 1,300 former players have died since the B.U. group began examining brains. So even if every one of the other 1,200 players had tested negative — which even the heartiest skeptics would agree could not possibly be the case — the minimum C.T.E. prevalence would be close to 9 percent, vastly higher than in the general population.

The N.F.L.’s top health and safety official has acknowledged a link between football and C.T.E., and the league has begun to steer children away from playing the sport in its regular form, encouraging safer tackling methods and promoting flag football.

44

Linemen

Daniel Colchico

Pete Duranko

Gerry Huth

Tom Keating

Tom Mchale

Joe O’Malley

Mike Pyle

John Wilbur

Linemen make up the largest share, by far, of those tested by Dr. McKee, partly because nearly half of the 22 players on the field are offensive and defensive linemen.

But that may not be the entire reason.

Linemen knock heads on most plays, and those who study brain trauma say the accumulation of seemingly benign, non-violent blows — rather than head-jarring concussions alone — probably causes C.T.E.

Data compiled by researchers at Stanford showed that one college offensive lineman sustained 62 of these hits in a single game. Each one came with an average force on the player’s head equivalent to what you would see if he had driven his car into a brick wall at 30 m.p.h.

Players pictured are publicly known to have had C.T.E.

7

Quarterbacks

Quarterbacks, the stars and most highly paid players in the league, are now provided more protection against hits to the head than other players. But that has hardly eliminated concussions and other blows to their heads. The quarterbacks still hit their heads hard on the turf when they are sacked, or take head-jarring hits when they leave the pocket to run.

The rules that provide more protection have only recently been established.

They were not in place when Ken Stabler was leading the Oakland Raiders of the 1970s.

Before Stabler died, at 69, of colon cancer in July 2015, he had requested that his brain be examined to see why his condition had been progressively slipping.

Dr. McKee found that he had a “moderately severe” case of C.T.E. The lesions were widespread, she told The Times.

From Ken Stabler’s Brain

The trauma of repetitive blows to the head triggers degeneration in brain tissue, including the buildup of an abnormal protein called tau. Thin slices of tissue are dyed and the tau shows up as these darker areas.

C.T.E. often affects the superior frontal cortex, an area important for cognition and executive function, including working memory, planning and abstract reasoning.

The insula may be involved in C.T.E. — an area of the brain important in emotion, social perception and self-awareness.

The amygdala is often severely affected. It is important in emotional control, aggression and anxiety.

C.T.E. frequently damages the mammillary bodies, an area important in memory.

13

Linebackers

The brains of the 13 linebackers shown here do not include the most high-profile of them all, Junior Seau. Seau, 43, whose brain was examined by the National Institutes of Health, killed himself with a gunshot to his chest in May 2012. Suicide is not uncommon among players who suffer the effects of C.T.E., but Dr. McKee and other researchers caution that no correlation between the two has been firmly established.

Linebackers, like linemen, sustain many sub-concussive blows to the head, the ones that show no immediate symptoms but can have a cumulative impact over time. Dr. McKee has said that linebackers who play in the league for 10 years could sustain upward of 15,000 of these sub-concussive hits.

17

Defensive Backs

Bill Bryant

Art DeCarlo

Dave Duerson

Jim Hudson

Robert Sowell

Demetrius Freeman/The New York Times

Tyler Sash was found dead of an accidental overdose of pain medications on Sept. 8, 2015. He was 27.

Sash had played safety for the Giants on their 2011 Super Bowl team after playing the position in college at Iowa. The Giants released him in 2013 after he sustained what was believed to be his fifth concussion.

“Those concussions are the ones we definitely know about,” his older brother Josh said. “If you’ve played football, you know there are often other incidents.”

Despite Sash’s young age, his family requested that his brain be examined for C.T.E. because he was showing uncharacteristic signs of confusion, memory loss and fits of anger.

Their suspicions were confirmed. Dr. McKee said at the time that: “Even though he was only 27, he played 16 years of football, and we’re finding over and over that it’s the duration of exposure to football that gives you a high risk for C.T.E. Certainly, 16 years is a high exposure.”

Age ranges at time of death

8

44

58

40 and younger

41 to 69

70 and older

Dr. McKee found the disease at a level similar to that found in Seau’s brain, and it was in the region of the brain that is consistent with the symptoms he was exhibiting.

Sash’s mother, Barnetta Sash, said: “Now it makes sense. The part of the brain that controls impulses, decision-making and reasoning was damaged badly.”

Players pictured are publicly known to have had C.T.E.

The One That Tested Negative

The family of the only N.F.L. player without C.T.E. in Dr. McKee’s study did not authorize her to publicly identify him.

The Complete Study

In addition to the 111 brains from those who played in the N.F.L., researchers also examined brains from the Canadian Football League, semi-professional players, college players and high school players. Of the 202 brains studied, 87 percent were found to have C.T.E. The study found that the high school players had mild cases, while college and professional players showed more severe effects. But even those with mild cases exhibited cognitive, mood and behavioral symptoms.

There is still a lot to learn about C.T.E. Who gets it, who doesn’t, and why? Can anything be done to stop the degeneration once it begins? How many blows to the head, and at what levels, must occur for C.T.E. to take hold?

“It is no longer debatable whether or not there is a problem in football — there is a problem,” Dr. McKee said.

Sources: VA Boston Healthcare System; CTE Center at Boston University; News reports. Images were not available for all brains.

Additional production by Jon Huang, Becky Lebowitz Hanger and Jeffrey Furticella. Additional reporting by Bill Pennington and John Branch.

original article: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/07/25/sports/football/nfl-cte.html